Once upon a Monday 🍵

Last night I went to a tea ceremony at a brownstone apartment on West 87th with six strangers. Everyone sat on the floor around a black stone table, which was overlain with a gauzy, ethereal runner. It was dyed with plants; there were petals in its wrinkles. Together, we all drank seven rounds of tea in silence. The man to my left—the one with a mane of curly grey hair—was wearing a stunning copper bracelet.

The bracelet was shaped like a C, with two large circles at both ends. It was thick, like rolled dough, and at least an inch wide. As it gleamed in the candlelight, I saw fine etchings along its sides.

When tea ended, I marveled at the bracelet. “Yes!” everyone said. We looked around at each other in communal admiration—we’d all been drawn to it.

“It’s really something, right?” he said. “Actually, there’s quite a story behind it.”

Of course there was.

“I have a friend whose work often took him to Africa. One day, he called me up and said, ‘Hey, I think I have something for you.’ He said he’d found a bracelet buried in a cache in the Sahara.”

The man raised his brows, a bit incredulous himself. But no matter. Be it with bracelets or friends or faith, we’re inclined to benefit the doubt when doubt is an adventure.

“The nomadic peoples of sub-Saharan Africa were skilled metallurgists. Which is astounding, when you consider that there aren’t many trees where they live. I mean, without wood, how did they procure charcoal to smelt copper?”

(One of my favorite things is when the Upper West Side mensch intelligentsia state obscure knowledge like this so matter-of-factly. Actually, I do not know metallurgy fundamentals? One time, at Zabar’s, a man was passing out fliers for his son campaigning for city council. “His last name Brancusi! You know, like the sculptor!” OH BUT OF COURSE)

The man continued: “One theory is that they made charcoal themselves with charred bones. Camel bones, sheep bones, any bones.”

Bones have a high calcium content, and in metallurgy, calcium is an excellent flux. When fired in a high-heat, low-oxygen environment, bones carbonize and can be burned like charcoal.

“You can imagine not just the talent, but the resources it would take to produce something like this. Whoever it belonged to would have been incredibly wealthy. Likely some kind of clan leader.”

I held the bracelet in my hand, tried it on, felt its weight on my wrist. I imagined it nestled in sand, and imagined the person made it. They were making their way in the harshest of worlds.

The things we carry say everything.

What did they carry across the Sahara? If I had to guess: as little as possible. A bit of food, a blanket, a tent, cookware, a weapon.

But bones? Rickety, unwieldy, heavy bones? I imagined them taking up valuable cargo space against a camel’s ribs, straining the seams of hand-stitched bags. All this for charcoal? To create something so seemingly trivial as a bracelet?

For generations, this jewelry was lost in the sands of time. But it was forged from a truth. And truth will not be buried.

Art is not peripheral. Beauty is not optional, but a strategy for survival.

It is written in the bones of the world. And it is written in ours.

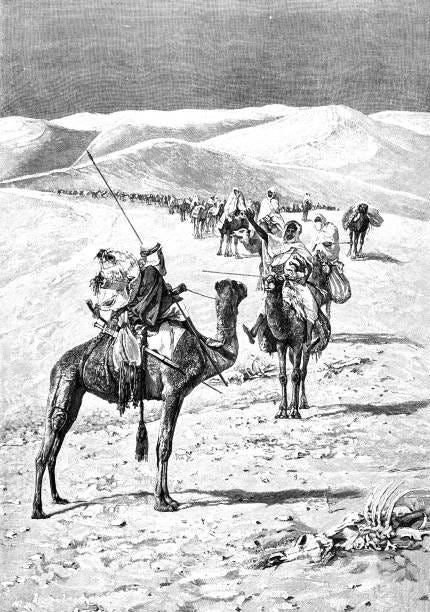

Above: An oil painting by Mariama, a self-taught Tuareg artist hailing from Azawagh, a dry basin in Niger. Many scholars believe metallurgy was independently invented here in 2000 BC, making it one of the world’s oldest metallurgies.

Thanks for reading Gemini Mind! Elsewhere, you can find me as @yokizzi 💫